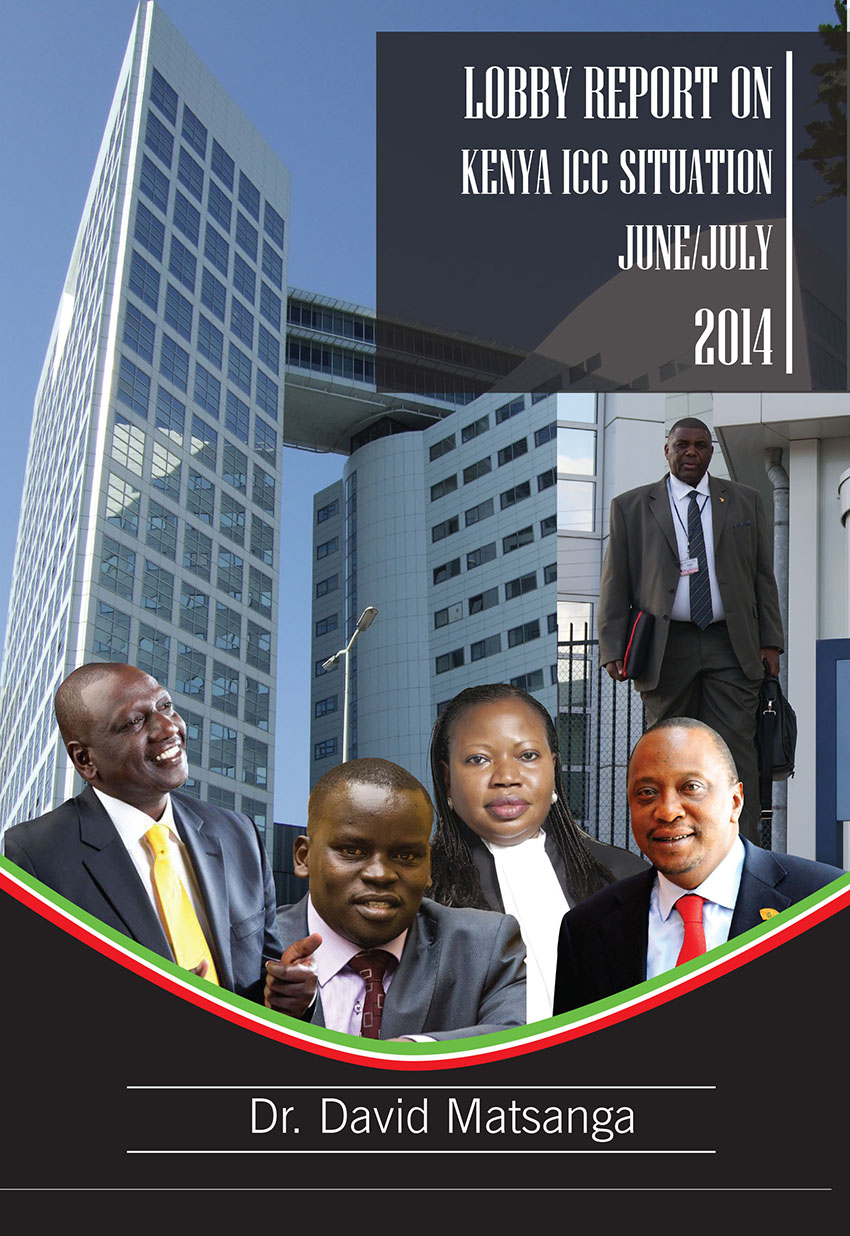

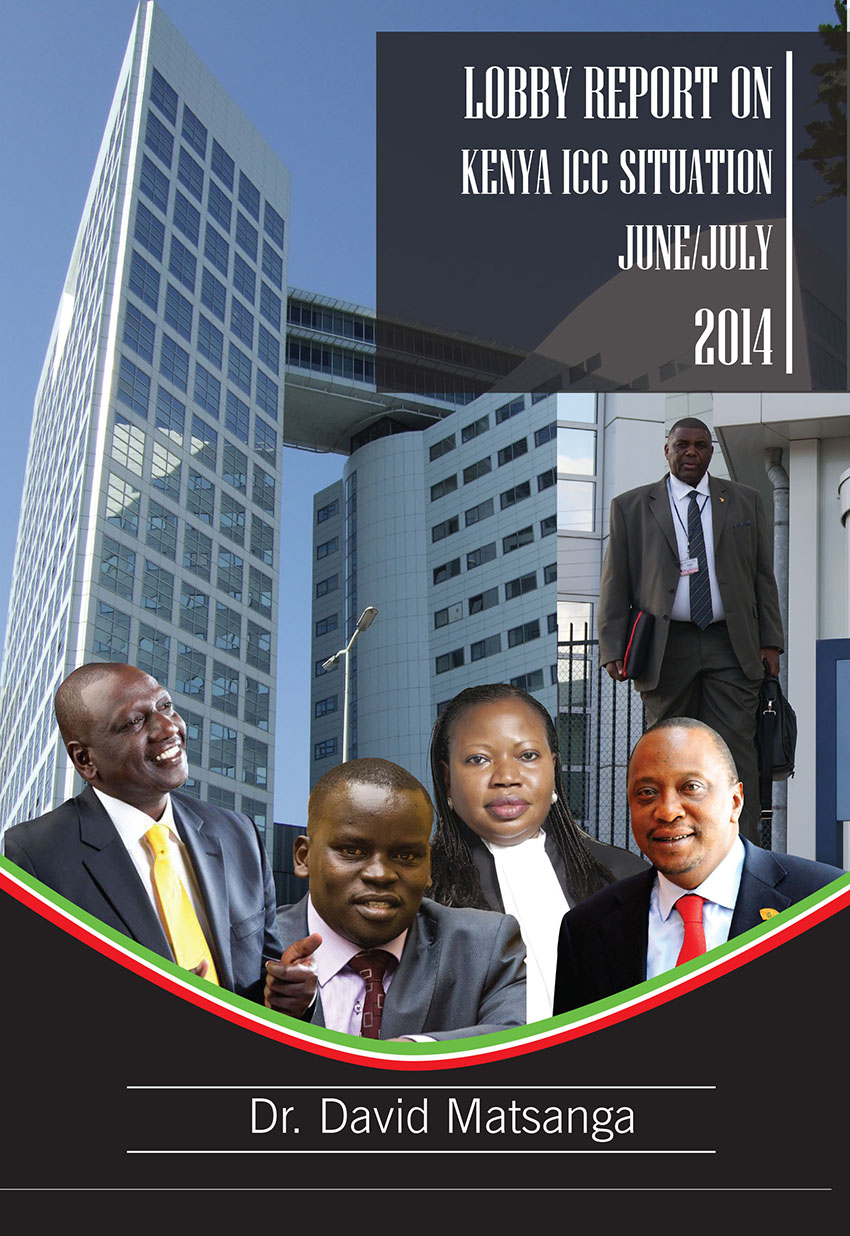

2307LOBBY REPORT ON KENYA ICC SITUATION JUNE/JULY 2014

Kenya governance is polarised by ICC intervention.

There is a recipe for disaster after post- trial era.

Retributive justice will bring more chaos than peace in Kenya

Are Kenyan ICC suspects the real suspects or framed ones?

Does Kenya situation qualify termination under Article 53 of the Rome Statue?

01. Acknowledgement:

This is my ICC lobby report to the world on Kenyan cases and implications of a full trial in both cases. The lobby report owes its greatest debt to the people of Kenya and Africa especially to the victims and suspects. The report would not be complete without the mention and thanks to many volunteers who provided information freely and friends in Kenya whom I cannot name for various reasons. My defence lawyer Chief Charles Taku, who did a tremendous job to comfort me during the time of ICC threats of using Article 70 on me by Luis Moreno Ocampo and Fatou Bensouda.

I want to thank the skills, patience and enthusiasm of many Kenyan volunteers in narrating some of the terrible stories that the OTP left out by design.I encountered many obstacles during my investigative journalism journey in Kenya that included OTP wanting to charge and silence me under Article 70 of the Rome Statute for allegedly exposing OTP 4 as a liar.

I want to say I was prepared and still prepared to be charged under Article 70 of the Rome Statute for tampering of witness OTP4 if ICC chief Prosecutor has any grain of salt left on these cases. The world must know that under “Confidential documents” before the Appeal 5 of ICC lies the truth about Kenyan cases. My interview with the ICC investigators provided huge materials that exposed the loopholes of a flawed investigation.

I Know friends and colleagues who were unstinting with their time, advice, and criticism. I am especially indebted to one lady whose work and writings, I used in researching and looking for the truth on these cases. I thank you so much for the brilliant materials that you provided on this subject of ICC when I embarked on the journey to expose faked and flawed investigations that today haunt the court and OTP.

For my family and especially my wife and children I say gratitude is inadequate expression. I owe you a break after Kenya ICC cases. I want to say here that quality is not desirable but worth striving to achieve. The ICC debacle placed me in state of confusion as I had to remove fiction from the truth. I want to thank senior comrades that I shared facts in hotels and other places in Kenya. Together we managed to find some facts that Luis Moreno Ocampo and OTP failed to point out.

Suspects and Victims:

I want to take this opportunity to thank the suspects and victims of PEV 2007-2008 who have been pained by the revelations that I discovered in my investigations. As a remarkable scholar on African politics I engaged the kind of direct probing that changes minds and opens new directions for further investigations and evidence collection.

Obstacles and defence teams:

The problems and obstacles that I encountered made me learn how to handle post- structuralism largely from literary scholars in law (defence lawyers and prosecution lawyers), which are problems of those like me who wanders in into new fields like ICC and law. I must add here that I am still confused as to why defence lawyers in both cases allowed these fake cases to go on and on when in actual sense they should have asked for early termination after it was discovered that all witnesses were liars and fake.

Adaptability and disciplinary paradigms:

The adaptability of reigning disciplinary paradigms, of the significance if any of the supposed and oppositions between those who understood the future consequences of ICC on Kenya and some people within Kenya who had different views was worrying me as Pan African and non-Kenyan.

The ICC, Judges and Fatou Bensouda:

Lastly I want to thank, the court of ICC, the Judges, and all the other lawyers, my own for listening and reading my documents and making historical judgements that will haunt ICC forever on the African continent. I want to thank Fatou Bensouda for the openness and frankness she exhibited even when telling lies about financial statements of President Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta. I also thank all my haters who inspired me to write this report.

Dedication:

I dedicate all my voluntary work on Kenya ICC cases to victims and suspects in PEV- 2007-2008. To my family and friends who assisted in Kenyan research I owe a lot after the end of ICC strangulation of Kenya.

My Overview:

- I have written this exit lobby report so that I go on record for having told the world about a fake trial that will create a Post –trial conflict in Kenya. The way ICC Chief Prosecutor and Trial Chambers V (a) and V (b) have handled the Kenyan cases by shifting goal posts and the courts allowing the shifting will cause a new conflict in Kenya if the corroded cases are not terminated now.

- It is important to understand why I became part and parcel of the Kenyan ICC situation. I am a volunteer investigative journalist who came across ICC malfunctions in the Uganda cases in 2005. I was Leader of the Peace Delegation and Chief Negotiator in the Uganda/LRA UN, EU, and AU sponsored peace talks in South Sudan Juba under Dr. Riek Teny Machar as UN, EU, AU, IGAD Chief Mediator. Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda was leader of Gou delegation and chief Negotiator of the GOU

- The first ICC warrants in Africa that were issued against Ugandan LRA side formed the basis of my courage and determination to stop ICC and Luis Moreno Ocampo (OTP) from doing the same in Kenya. Not because I supported what LRA did in Uganda but because of the manner in which Luis Moreno Ocampo investigated the Uganda cases that gave me faith to expose ICC. Both sides in the Uganda conflict committed crimes that were not investigated properly by ICC.

- It is good that President Museveni in his entire militancy format accepted peace talks for the sake of Ugandan and we sat down and discuss the Ugandan conflict whose peace has returned in Northern Uganda and of which I am deeply associated and grateful with. That is the courage I took when I decided to go and look for LRA leadership and bring them on table so that my people of Uganda have peace forever.

- It must be noted that LRA committed heinous crimes but method used by Luis Moreno Ocampo to determine and find evidence was very flawed and bungled in all forms that is why Ugandans decided to have restorative justice instead. As President Museveni said at “Kasarani we lost thousands of people” but we did not opt for ICC route only we went for alternative local justice mechanisms as redemption strategy against the monster ICC.

- The Uganda case was “classic legal robbery” where Luis Moreno Ocampo and OTP investigated both sides and got incriminating evidence from both sides but decided to charge one side which OTP alleged had committed serious atrocities and never told us about the other the investigations on the other side.

- In Bosnian war both sides were brought before the trial Chambers but in all cases that Ocampo has handled in Africa, it is has been a one sided show. This unfairness was seen in Kenyan cases where the main suspects under international law were left and weaker or wrong suspects were charged. That made me determined to find out the truth.

Ratified the Statute:

- The Republic of Kenya ratified the Statute of the International Court (herein the ICC) on 15 March 2005. Like a majority of African countries that ratified the Rome Statute, Kenya had good cause to be proud of her exercise of sovereignty on this matter. Kenyans like many Africans thought that this was the best hope to tame impunity in Africa.

-

- The sad events that occurred over thousands of miles away in Rwanda and Sierra Leone where hundreds of thousands were massacred in the “collective madness” that afflicted those African countries were still green in the collective memory of many in Kenya and on the African continent.

- Kenya and Africa carefully followed the evolution of the trials conducted at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the Special Court for Sierra Leone and believed that if anything, international criminal justice could be a reasonable bar to impunity. It was believed that international Criminal Justice could bring justice and reconciliation to these countries and the continent of Africa, also called the troubled continent.

- On December 27, 2007 to February 28, 2008, Kenyans experienced their own dose of “collective madness”. This occurred after a contentious election in which some 1,300 Kenyan citizens were alleged to have been killed and some 250,000 allegedly displaced. Led by the African Union, the International Community scrambled to douse the flames of conflict. These efforts succeeded in bringing a negotiated solution to the political crisis.

- In the heat of the conflict, even before a negotiated solution was implemented, the Prosecutor of the ICC Mr. Luis Moreno Ocampo colluded with the then Chief Mediator Dr. Kofi Annan and announced their intentions to conduct a proprio motu investigation in the “Situation in the Republic of Kenya” under article 15 of the Statute of the ICC.

- On November 26, 2009, Luis Moreno Ocampo filed the “Request for authorization of an investigation pursuant to Article 15” in which he requested the Chamber to “authorize the commencement of an investigation into the situation in the Republic of Kenya in relation to the Post-election violence of 2007-2008”. (My emphasis)

- The decision by the Prosecutor of the ICC to interject such proceedings into the politically charged election violence, the timing of his decision, and the evolution of the cases that followed are the subjects of scrutiny in this lobby report to the world.

2. Introduction:

- I have read and followed Professor Nancy Armoury Combs (2010) who stated that, “International criminal justice was, in sum, the subject of a great deal of soaring and inspirational rhetoric but in recent years, the glow surrounding international criminal justice has begun to fade”.

- Citing developments at the ICC, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the Special Court for Sierra Leone among others, she concluded “many have begun questioning the ability of international criminal tribunals to achieve many of the goals that previously had been reflexively attributed to them”.

- Professor Combs asserted that recent research has called into question the ability of international criminal tribunals to advance reconciliation and peace-building efforts following large scale violence.

- Despite the loss of faith in international criminal justice, in particular by Africa, the distinguished author concluded: “even if they regularly fail to deter, rehabilitate, or reconcile, international trials have at least been considered useful mechanisms for determining who did what to whom during a mass atrocity”.

- The developments in the “Situation in the Republic of Kenya” at the ICC have provided a reasonable basis for the frustrations and indictment of international criminal justice in the terms depicted by Professor Nancy Combs. ICC stands at cross roads and could collapse because of the flawed manner in which OTP conducted on most of the African cases and especially the fake cases of Kenya.

3. Beyond the rhetoric of Fatou Bensouda lies a litany of falsehood.

- The Prosecutor of the ICC Fatou Bensouda and a significant component of Non- Governmental Organizations(NGOs), Special Interest groups, Human Rights Organizations and Political Activists in and out of Kenya have made public allegations about “unprecedented levels of interference” by the Kenyans accused with Prosecution witnesses and evidence.

- The Prosecutor alleged the politicization of the cases by the African Union, the Government of Kenya, and alleged lack of cooperation by the said government in supporting her several requests to gather evidence within the territory of the Republic of Kenya. She alleged the intimidation of protected witnesses and their families. But did not tell the world how she also bought witnesses and kept on changing goal posts.

- The Prosecutor specifically alleged defense interference with witnesses whom she later withdrew in Case No. 1 and Case No. 2 . Challenged by the defense to prove the allegations of the unprecedented levels of interference with prosecution witnesses, the Prosecutor in reaction, applied for a warrant for the arrest of one of its own intermediaries Mr. Walter Barasa .

- There are significant underlying reasons that may explain why these allegations notwithstanding, the Kenyan cases are falling apart. Some of the reasons arise from the Prosecutor’s theories of the cases and significant pre-trial case managements missteps. Key Prosecutorial decisions taken at the initial stages of the cases might have contributed to the dire situation the ICC finds itself regarding these and some ICC African Situations .

- Beyond the rhetoric behind these allegations, the Prosecutor made a conscious decision to interject in a highly volatile political situation and politicized the case from inception. The Pre-trial Chamber was concerned that the proprio motuintervention in the Situation in the Republic of Kenya could be politically motivated.

- In raising this problem at the earliest possibility, the Pre-trial Chamber echoed the fears expressed by a number of State Parties during discussions leading to the Rome Statute in 1998. In this regard, the Pre-trial Chamber stated:

- “Thus, it suffices to mention that, insofar as proprio motu investigations by the Prosecutor are concerned, both proponents and opponents of the idea feared the risk of politicizing the Court and thereby undermining its “credibility”. In particular, they feared that providing the Prosecutor with such ‘excessive powers” to trigger the jurisdiction of the Court might result in its abuse”.

- The Chamber struggled with this crucial problem and concluded that in the exercise of its “supervisory role over the proprio motu initiative of the Prosecutor to proceed with an investigation”it can fulfil this function by “applying the exact standard on the basis of which the Prosecutor arrived at his conclusion” that there “is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation” .

- The Chamber in this decision reasonably perceived that politics could complicate the case (as indeed it has) and unsuccessfully attempted to resolve. Unfortunately, the legal threshold established by the Chamber in the confirmation of charges introduced considerable pitfalls in the cases which the Prosecutor might not have anticipated or foreseen at the time.

- The Pre-trial Chamber appropriately identified the potential political underpinnings of the Prosecutor’s proprio motu intervention, but failed to define or set the limits between the politics, the crimes and the law of the cases. Rather, the Chamber compounded the problem by merely rubberstamping the very low threshold of Kenyan cases on the basis of which the Prosecutor’s application was grounded .

- In paragraph 52 of the confirmation of charges decision, the Chamber noted that “the drafters of the Statute established progressively higher evidentiary thresholds in articles 15, 58 (1), 61(7) and 66 (3) of the Statute”.

- The Chamber, by deferring to article 15 in this hierarchy of evidentiary thresholds effectively endorsed the threshold established at the authorization of investigation for the confirmation of charges. In this regard, the Chamber specified that “the evidentiary threshold applicable at the present stage of the proceedings (i.e. “Substantial grounds to believe”) “is higher than the one required for the issuance of a warrant or summons to appear but lower than that required for a final determination as to guilt or innocence of an accused”.

- The progression of thresholds established in this case led to the rubberstamping of the Prosecution’s applications and the charges during the Pre-trial proceedings. There can therefore be no gainsaying that the legal processes that occurred at the pre-trial stage of the Kenyan cases were not subjected to reasonable scrutiny. The failure in this regard might be haunting the trial processes as the Prosecutor struggles to circumvent the pit holes that the cases were consigned to at that phase of the case.

- This problem is not uncommon in International Criminal Tribunals. David Tolbert and Fergal Gaynor stated that “the Statutes of the Tribunals require a judge to confirm an indictment brought by the Prosecutor, applying a prima facie review standard as laid down in the ICTR Statute Art. 19(1).

- This requires a judge to be satisfied that the material submitted by the Prosecutor provides a “credible case, which would (if not contradicted by the defense) be a sufficient basis to convict the accused on the charge” (Prosecutor v Haradinaj et al, 2007 at par. 22 and Prosecutor v Popovic et al 2006 para 36 ).

- The application of this standard has inevitably resulted in the confirmation of the indictment and is seen in many cases as simply a “rubber stamp”. The authors were concerned that the “Statutes of the Tribunals do not require judges to have any trial experience, nor is any judicial training mechanism in place for trial experience. Pre-trial judges should be more involved and make efforts to be familiar with the case to ensure that it is trial ready for trial”

- Tolbert and Gaynor strongly advised that “given the seriousness of the charges in international tribunals, and the importance of the cases both to the charged persons and the victims, there is an argument that the standard should be set at a higher level and indictments subject to more intense scrutiny before confirmation.

- This may help in stopping weak cases from going forward, which result in lengthy pre-trial detention and where acquittals or low sentences result in disappointment to victim groups” .Rubberstamping the Prosecutor’s “conclusion” in the decision authorizing investigation in the post-election violence in the Republic of Kenya, the Chamber reasoned “The Chamber, in turn, is mandated to review the conclusion of the Prosecutor by examining the available information, including his request, the supporting material as well as the victim’s representations collectively, the “available information” if, upon examination, the Chamber considers the “reasonable basis to proceed” standard is met, it shall authorize the commencement of the investigation”.

- This low threshold established during pre-trial proceedings facilitated the admission without serious scrutiny of questionable evidence to confirm charges against the accused. Statements provided by Witness OTP4 in case No 2 and witness OTP 11 and OTP 12 in case No 1 fell in this category.

- The defense provided compelling evidence during confirmation of charges proceedings that significantly undermined the credibility and reliability of these witnesses. The Chamber nevertheless proceeded to admit their testimonies based on this low threshold. The Prosecutor has since established that these witnesses lied in statements they provided to the Prosecutor during the pre-trial proceedings and dropped them from the trial proceedings.

- Nevertheless the Prosecutor proceeded and is still proceeding with the trials on the basis of charges that were confirmed using the false statements while alleging without proof “unprecedented levels” of interference with a number of prosecution witnesses that include these individuals.

- The perception by victims and the public in Kenya that some legal representatives of victims participating in the proceedings were not acting as independent voices of the victims may have contributed to a loss of faith in the trial proceedings. Some of the legal representations have adopted controversial positions presented by the Prosecutor at trial most of the time.

- Victims required independent voices to strongly present their case independent of that of the Prosecutor. Pre-trial Chamber 1 defined the role of legal representative of victims in the Lubanga Case as follows: Para. 51,” In the Chamber’s opinion, the Statute grants victims an independent voice and role in proceedings before the Court. It should be possible to exercise this independence, in particular vis- a- Vis the Prosecutor of the ICC so that victims can present their interests. As a European Court has affirmed on several occasions, victims participating in criminal proceedings cannot be regarded as “either the opponent-or for that matter necessarily the ally-of the prosecution, their roles and objectives being clearly different”. The perception that the supposedly independent voices of common victims’ representatives have not been heard on a number of legal and evidentiary issues touching on the interest of victims has tainted public perception of the trials.

3. Stepping on sensitive political, ethnic and cultural nerves in Kenya

- The Prosecutor Mr. Luis Moreno Ocampo chose the public media as a platform to lay out his cases from the moment he made his intention to intervene in the Situation in the Republic of Kenya. In so doing, he made the media a legitimate arena for the litigation of the cases. This venue of choice attracted a plethora of participants; some intended, others not. The media has since influenced public opinion on the cases in ways unimagined.

- A significant media influence arose from the decision by the Prosecutor to recruit some media practitioners as intermediaries in conducting investigations. The evidence collected through this process was presented before the Pre-trial Chamber for confirmation of charges against the accused and in the unfolding trials. Mr. Barasa a Journalist practicing in the Rift Valley against whom the Prosecutor has secured a warrant for his arrest and transfer to the court for witness tampering, was recruited by the same Prosecutor to help in gathering evidence against accused in case number one.

- It is unclear how this suspect tampered with witnesses he had a mandate from the Prosecutor to recruit. It is hoped that the proceedings against him when and if they occur, will open a window to the world about the manner and tactics the Prosecutor used to collect the evidence she is relying on to pursue these prosecutions. It may reveal a consistent pattern of questionable prosecutorial tactics that a Trial Chamber of the ICC criticised and warned against in the Lubanga trial.

- In his public media statements and in public court documents, the Prosecutor laid out his case in political, cultural and ethnic terms . Dressing alleged crimes in political, cultural and ethnic robes carried significant risks. An obvious risk was the possibility that alternative explanations might exist for the existence of these factors during the election violence. The alternative explanations could undermine the Prosecutor’s theories of the cases.

- The Prosecutor disregarded the political trends and shifting political alliances that are known influential factors in Kenyan politics. Like past elections, these factors were present during the election in which the alleged crimes occurred.

- The presence of these unpredictable political trends significantly undermined the theoretical relevance of alleged ethnic allegiance and cultural homogeneity that were alleged as facilitators of the alleged crimes. Contrary to this theory, the political forces that existed during the elections transcended alleged ethnic and cultural compartments in which the alleged crimes were locked.

- All ethnicities in Kenya militated in all the political parties, fielded candidates in the elections and reacted different to victory and defeat in their respective constituencies. The fact that some of the parties commanded a majority within distinct ethnic and cultural groups in locations where the crimes were alleged did not undermine this reality.

- This significant factor was not seriously considered, and where considered was not given the attention it deserved.

- The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was confronted with a similar situation in the case of The Prosecutor V Augustin Ndindiliyimana, Augustin Bizimungu, Francois-Xavier Nzuwonemeye and Innocent Sagahutu . In that case, the Prosecutor struggled to explain every conceivable crime that occurred in Rwanda in 1994 in ethnic terms.

- When the ICTR was established, UN investigative reports held the Rwandan Patriotic Front accountable for the crimes that led to the extermination of hundreds of thousands of Hutu, in particular in areas that were entirely under the RPF occupation throughout the war.

- Unlike the ICC Prosecutor, the ICTR Prosecutor acknowledged that serious crimes were perpetrated against the Hutu and promised to investigate. Recognising the occurrence and magnitude of these crimes and undertaking to investigate, at first gave the investigations, a presumption of legitimacy. Regrettably, the tyranny of victors’ justice left the ICTR Prosecutor struggling to place the responsibility for the crimes that were perpetrated against Hutu victims whom the Prosecutor categorized as “moderates” on other Hutu whom she purported to identify and categorized as “extremists”.

- At the trial, the Prosecutor did not convincingly explain or establish the circumstantial categorisation of Hutu into “moderate” and “extremist”. The Prosecutor failed convincingly to account for the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Rwandan citizens of Hutu and Twa ethnicity. He failed to justify his inability to investigate and prosecute alleged perpetrators of the crimes.

- Like the ICTR, the inability of the ICC Prosecutor to conduct proper investigations into all the crimes alleged significantly undermined her claims of seeking justice for victims and her alleged record of fighting impunity.

- It may reasonably be discerned from Mr Ocampo’s several press statements, he intervened in the Kenya political arena when the perpetration of crimes was ongoing with a pre-conceived list of suspects and a case theory that perceived the crimes in ethnic terms. Once he sought and got permission of the Pre-trial Chamber to open investigations, he found no need to conduct proper investigations to obtain credible evidence against all perpetrators of all crimes irrespective of ethnicity, or other discriminatory grounds. In the result, the cases he brought for trial lacked legitimacy in the eyes of a sizeable component of Kenyan citizens and victims. This may explain the lack of support the cases may be experiencing among the victims, witnesses and the public at large.

- The alleged ethnic, cultural, political, factual and theoretical foundations of the cases were therefore, mired in serious controversy from inception.

- On or about September 10, 2013, the Prosecutor delivered her opening statement in case number one of Deputy President William Ruto and Journalist Arap Sang. The said statement was illustrated by among other evidentiary material, videos of the Kalenjin elders in session performing traditional rites.

- What the Prosecutor failed to give serious consideration when laying out her case was the potential backlash of criminalizing aspects of the Kalenjin and Kikuyu culture and traditions might cause. By alleging that Kalenjin initiation rites and protected cultural practices were used to perpetrate or facilitate the perpetration of crimes alleged in the indictment was a serious misjudgement.

- The Prosecutor came out in the view of many Africans across the continent as culturally insensitive. The misjudgement in this regard could potentially persuade some victims, witnesses and their families to decide against participating in the trial process.

- Evidence concerning sensitive aspects of the culture and traditions of victims, witnesses and the public at large Special was treated at the Court for Sierra Leone and the ICTR, with caution. Exposing to the world, evidence on the initiation rites of a people and other aspects of their culture considered sacred is considered in most of Africa, a serious affront on cultural identity of the people.

- Alexander Zahar and Goran Sluiter (2008) offered the following unpleasant opinion on a finding in the introductory section of the Akayesu judgment at the ICTR: “In the introductory section of the Akayesu judgment, which offers a potted history of Rwanda, we are told that in the early twentieth century the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was based on lineage rather than ethnicity. We are told not consistently that the demarcation line was blurred (one could move from one status to another”. In footnote 11, the authors described this finding as “simplistic, tendacious, at times incoherent and full of inaccuracies”.

- The safeguarding and protection of African cultures and traditions have been at the centre of African consciousness. Frantz Fanon decried the fact that “the indigenous population of Africa is discerned by the west as an indistinct mass”. Senghor wrote that the role of the intellectual has at least two responsibilities in his society: “first, to perceive what is good for his country, while holding intact the traditions of the past. The intellectual is one who must, in order to have a true national consciousness, be aware of his tradition and the sources of his past, a past which is still relevant even as he creates in reaction to it”.

- Wilfred Cartey and Marin Kilson writing about advocates of African heritage stated that “to validate one’s heritage, to explore one’s culture, to examine thoroughly those institutions which have persisted through centuries is perhaps the first step in a people’s search for independence, in their quest for freedom from foreign domination. Such a validation, such an exploration and examination is resolutely undertaken at the turn of the nineteenth and beginning of twentieth century by four Africans, Casely Hayford, Jomo Kenyatta, James Africanus B. Horton, and Edward Blyden.”

- This spirit was and is alive in Kenya and most of Africa. It is the driving force of Africa renaissance and the ongoing struggle for freedom from the pervasive influences of neo-colonialism in the continent. The cultural sensitivities transgressed in laying out the Prosecutor’s case in these cases cannot therefore be minimized or wished away.

- There is no gainsaying that prior to intervening, the Prosecutor seriously considered the political implications of his decision. Some of the intermediaries whom the Prosecutor relied on to gather evidence in these cases have been publicly identified as participants in the contentious elections that led to the violence in 2007-2008.

- They again participated in the last elections, which the accused and their supporters won resoundingly. Their involvement in the cases was bound to be problematic. This category of individuals has sustained the political spotlight and media frenzy on the cases.

- The theory of the cases around the land disputes involving the different ethnicities in the conflict areas is not only sensitive matter, it carries a significant political implication. The problem is undisputable tied to Kenya’s and Africa’s colonial past with ongoing ramifications. Jomo Kenyatta spoke for his people but also for the entire continent when he aptly underscored the highly political nature of the land problem.

- The first President of Kenya on July 26, 1952 during a rally organized by the Kenya African Union at the Nyeri Show grounds attended by a crowd of 30.000 people did not mince his words. Jomo Kenyatta decried the fact that in the Kikuyu country, nearly half of the people were landless and had an earnest desire to acquire land so they have something to live on. The Africans, Jomo Kenyatta said “had not agreed that this land was to be used by white men alone. He went on, “Peter Mbitu is still in the UK where we sent him for land hunger. We expect a Royal Commission to quickly inquire the land problem” .

- Bringing up the land issue as a factor in the election in 2007-2008 and criminalizing it, gave the accused a talking point, which resonated with popular sentiments. It equally sparked tensions and mobilized opposition against the cases brought against the accused. The fact that during this period some surviving Mau Mau fighters were pursuing a long standing case against the British Government for the crimes Jomo Kenyatta denounced during the rally at Nyeri Show Grounds on July 26 1952 carried symbolic weight.

- Considered separately or in aggregate, prosecutorial case management misjudgements and a limited knowledge of the political and cultural environment in which the alleged crimes were perpetrated, provided an alibi for the charge of a neo-colonial conspiracy to have the accused jailed.

- The political, ethnic and cultural foundations on which the prosecution is based has played to the fears of many people in Africa and Kenya in particular that the prosecutions are neo-colonial manoeuvres to deny them and the people of Kenya the benefit of credible leadership which the accused secured the Kenyan peoples’ mandate to provide.

- The charge about a neo-colonial conspiracy to use the ICC process to effect regime change, has since become the rallying cry in the continent for those opposed to the ICC selective prosecutions targeting Africans.

- Many vividly remembered the prophetic premonition of Osageyfo Kwame Nkrumah concerning the vulnerability of many African countries and the threat posed to their sovereignty by neo-colonialism: “This arrangement gives the appearance of nationhood to African territories but the substance of sovereignty rests with metropolitan power. The creation of several weak and unstable states in Africa it was hoped, would ensure the continued dependence on the former colonial powers for economic aid, and impede African unity” .

- The following statement by Nwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere confirmed these fears and enjoined Africans to summon the values of the past to redress the challenges of the moment: “Although we do not claim to have drawn up a blueprint of the future, the values and objectives of our society have been stated several times” . The perception of insensitivity to these African values by the ICC prosecutor is a Launchpad for the opposition to the ICC Kenyan cases on the African continent led by some influential progressive forces present on the continent.

- The politics of the ICC Kenya cases are further compounded by the controversial double standards established by other political actors involved in these and other cases at the ICC. An article in the New York Times on June 2, 2014 illustrates this point. US Ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power expressed outrage against the Soviet Federation for vetoing a Security Council Resolution referring the Situation in Syria to the ICC. Ambassador Samantha Power stated:

- “Our grandchildren will ask us years from now how we could have failed to bring justice to people living in hell on earth”. According the journalist, her remarks “were part of an unusual American push to widen the reach of the global tribunal”.Emphasizing the hypocrisy and political motivations surrounding this supposedly pro-ICC stand, the journalist stated:

- “That perception could not come at a worse time for a court whose biggest challenge is to convince the world that its investigations are not directed by politics. It has been criticized for indicting a disproportionately large share of Africans. It has won only two convictions in the course of a decade. It has been unable to apprehend several men it has indicted-including the former Libyan dictator Co. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s son, Seif al-Islam el-Qaddaffi, whose investigation the United States Supported” .

- Conclusion and Recommendations to the world for action :

- The Situation in the Republic of Kenya has dominated the agenda of the Prosecutor of the ICC for more 6 years. The flawed manner in which the cases, evidence, and witnesses were collected lives a lot to be desired. This preoccupation has diverted the attention of the Prosecutor from crimes falling within the jurisdiction of the Court in other parts of the world.

- The extraordinary problems facing the Chief Prosecutor in these cases arose from significant misjudgements that occurred at the Pre-trial stage of the proceedings and therefore to save the Court we need stop the proceedings now. These misjudgements were overlooked or were not subjected to the degree of serious scrutiny by Pre- Trial judges as required in cases where serious crimes are alleged.

- The integrity of witnesses and significant aspects of the evidence they provided were called into question during pre-trial proceedings requiring further investigation. The lack of cultural sensitivity and awareness has impacted negatively on the image of the ICC and the integrity of the cases. Alleged “unprecedented levels of interference” and the intimidation of witnesses and their families cannot reasonably be said to be the sole reason for the problems the Prosecutor is facing in these cases.

- Many of these problems were inherited from the former Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo who should stand trial for perjury. The current Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda therefore has reasonable cause to seriously consider whether it is worthwhile proceeding with these cases under these circumstances that I have explained above.

- Equally, Her Majesty’s Government of United Kingdom (Britain) a country that has historical links with Kenya must not lose this country where the British have done a lot to maintain without for over 50 years. The faked and flawed ICC cases should not be teaming up with the great vision of civilization of our Great Nation of Britain. Britain which has given most of us in the world hope and faith must stand up and refuse to be dragged into an inferno lies where great values will be lost.

- The ICC indictments that were done in bad faith must be rejected by civilized countries in Europe because the set a wrong precedent. Britain must not drive the people of Kenya to look elsewhere because of silly diplomatic mistakes that were done by the USA in supporting ICC to recruit witnesses from USAID Kenya which has come to haunt the trials at The Hague.

- The Nation of Kenya today stands at crossroads where many of the citizens are polarised because of these ICC indictments that have caused a lot of mistrust within the political and democratic governance of the nation. This could lead to POST-TRIAL CONFLICT IN KENYA

- Kenya today is faced by threats of both “rented terrorism” from local political players and external Al- Shabaab terrorists who still roam at large on the porous border between Kenya and Somalia. The threats are real and could affect the entire region of East Africa and Great Lakes Region which relies on the peace and tranquillity of Kenya.

The International community, Britain, USA, France, Germany, AU, UN, and all other agencies MUST read this report and is directed to you and I will be honoured to deliver this Exit Report on Kenya directly to these countries starting from 18th July 2014 in an effort to lobby the world to do something to save Kenya from another Post –Trial chaos.

Thanks

Dr. David Nyekorach- Matsanga.

London - UK

Tel: +447930901252

Tel: +254723312564

africastrategy@hotmail.com.

dr.davidmatsanga@yahoo.com.

www.panafricanforumltd.com.

www.africaworldmedia.com

www.africaforumonicc.com

The prosecution has ‘rights’ to initiate investigations (on his own initiative) into a case, where they deem it necessary and in accordance with the law. See for this purpose, article 15 of the Statute of the ICC.

ICC -01/09/19 Paragraph 26 of Decision Pursuant to Article 15 of the Rome Statute on the Authorization of an Investigation into the situation in the Republic of Kenya.

Fact –Finding Without Facts: The Uncertain Evidentiary Foundations of International Criminal Convictions, Nancy Armoury Combs (2010) Cambridge University Press p 3-4.

The accused in this highly politicized case include high profile personalities like the current president of Kenya H.E Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy Mr. William Ruto and Arap Sang.

ICC-PIDS-CIS-KEN-01-012/13; The Prosecutor V William Samoei Ruto and Joshua Arap Sang.

ICC-PIDS-CIS-KEN-02-010/11; The Prosecutor V Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta.

ICC-01-01/09-01/13; The Prosecutor v Walter Osapiro Barasa (warrant issued on 2 August 2013 and unsealed on 2 October 2013).

I cite for this purpose; ICC-01/04-01/07 the Prosecutor v Germain Katanga; ICC-01/01/11-01/11 the Prosecutor v Saif Al-Islam Gaddafi; and ICC-02/11-01/11 the Prosecutor v Laurent Gbagbo.

ICC-01/09-19, Decision Pursuant to Article 15 of the Rome Statute, on the Authorization of an Investigation into the Situation in the Republic of Kenya.

Para 24 supra, and para 52 of the ICC-01/09-02/2012 the Prosecutor V Francis Kirimi Mathaura, Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta and Mohammed Hussein Ali, 23 January 2013.

Para 52 of the Decision supra.

These are both ICTY cases in which is reflected the Prima Facie Review Standard as embodied in Article 19(1) of the ICTR Statutes.

Tolbert, David and Gaynor, Fergal (2009): Pre-trial: Greater Scrutiny Before Confirmation of Indictment; Pre-trial Management Use of Pre-trial Chamber or Judge in A Critical Assessment of International Criminal Courts ed Magda Karagiannakis, La Trobe University Federation Press (2009) P 39.

ICC- Situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pre-trial Chamber 1, Decision on the Application for Participation in the Proceedings of VPRS 1, VPRS 2, VPRS 3, VPRS 5, and VPRS 6, 17 Jan. 2006.

Judgment of Trial Chamber 1 in Prosecutor Vs Thamas Lubanga Dyilo, dated 14 March 2012, Decision on Intermediaries, 13 May 2010

The Prosecutor Mr Ocampo was also rebuked by the Pre-trial Chamber in the Situation in Libya due to prejudicial press statements made by him which infringed on the suspects rights to fair trial

ICTR-00-56-T The Prosecutor V Augustin Ndindiliyimana, Augustin Bizimungu,Francois-Xavier Nzuwonemeye and Innocent Sagahutu . The Trial Chamber entered a conviction and convicted the accused to various terms of imprisonment. On appeal, Co-Counsel Beth Lyons and I obtained a reversal of the conviction of Major Francois-Xavier Nzuwonemeye and an acquittal entered in his favour, more than 12 years after he was arrested in France and transferred to the jurisdiction of the ICTR.

Zahar, Alexander and Sluiter (2008), Genocide Law: An education in Sentimentalism; The problem with the Group, Oxford University Press p 158.

The Wretched of the Earth (New York, 1966): The Intellectual Elite in Revolutionary Culture at p 126.

The role of the intellectual in independent Africa: The articulators of freedom p. 124.

Cartey, Wilfred and Kilson, Martin (1970): The Africa Reader: Independent Africa, Random House, New York at p 3.

Kwame Nkrumah (1964) Neocolonialism: Africa Must Unite p 217 as reproduced in n 3 p 200-208.

Julius K. Nyerere (1967): Education for self-reliance. Gov. Printer Dar Es Salaam. March 1967 Gov. Printer Dar.

|